Commanding Officers

A long history and bright future!

The officers listed below commanded the USS Shields. The ranks given are the ranks of the commanding officer while onboard. Many commanding officers were later promoted. In particular, Paul Walter Rohrer and Albert Francis Hllingsworth both became admirals.

CDR George Bernard Madden Feb 8 1945 – Jun 12 1945

…Pictured in the photos to the right cutting the commissioning cake

LCDR George Thornhill McDaniel Jr. Jun 12 1945 – Oct 22 1945

LCDR Marcy Mathias DuPre III Oct 22 1945 – Jun 14 1946

LCDR Miles Rush Finley Jr. Jul 15 1950 – Apr 2 1952

CDR William Sherman Kirkpatrick Jr. Apr 2 1952 – Mar 20 1954

CDR Leigh Cosart (Early) Winters Mar 20 1954 – Mar 23 1955

CAPT Robert Henderson Holmes Mar 23 1955 – Apr 7 1955

CDR Albert Francis Hollingsworth Apr 7 1955 – Apr 5 1957

CDR Richard Morgan Wright Apr 5 1957 – Mar 8 1958

CDR Samuel Lewis Morton Mar 8 1958 – Apr 4 1960

CDR Arthur LaGrange Battson Jr. Apr 4 1960 – Mar 13 1961

CDR Joseph Lewis Sperandio Mar 13 1961 – May 2 1961

CDR Arthur LaGrange Battson Jr. May 2 1961 – Sep 13 1961

CAPT Robert Lee Wessel Sep 13 1961 – Apr 18 1963

CDR Howard Jackson Ursettie Apr 18 1963 – Sep 17 1964

CDR Victor Gordon Warriner Sep 17 1964 – Oct 23 1965

CDR John Francis Tarpey Oct 23 1965 – Apr 8 1967

CAPT Paul Walter Rohrer Apr 8 1967 – Oct 28 1968

CDR Robert Joseph Forsyth Oct 28 1968 – Jun 17 1970

CDR Billy Banks Traweek Jun 17 1970 – Dec 10 1971

CDR William Frederick (Fritz) Wolff Dec 10 1971 – Jul 1 1972

Notes:

| 1. | This data courtesy of Wolfgang Hechler & Ron Reeves |

| 2. | SHIELDS had no Commanding Officer during her four-year period in mothballs from 14 June 1946 until 15 July 1950. |

The Commanding Officer (CO) of a destroyer under peacetime conditions is normally a Commander with 15 to 18 years of commissioned service. During World War II, the commanding officer was frequently a Lieutenant Commander with far less experience.

Regardless of rank, the Commanding Officer was always referred to as “Captain.” He bears total responsibility for the ship and had commensurate authority over everyone on board. He was always on call when the ship was underway. He had non-judicial powers over all personnel under his command (Referred to as “Captain’s Mast”) or he could convene a summary or special court martial. His direct superior in the chain of command was his squadron or division commander who was normally a Captain with the honorary title of “Commodore”. If the ship was designated as a flagship, accommodations were provided on board for the Commodore and his staff.

The Executive Officer (XO) is the second in command on the ship. He functions as the administrator of the ship and has overall responsibility for all personnel on board. The Executive Officer is the person who is responsible for making things happen. He promulgates the plan of the day and oversees virtually every evolution. He does not normally stand watch underway. On many smaller ships, he usually doubles as the ship’s navigator. More about this later. The XO is often the resident “bad guy” in the wardroom because many COs like to play the “Good Cop/Bad Cop” game.

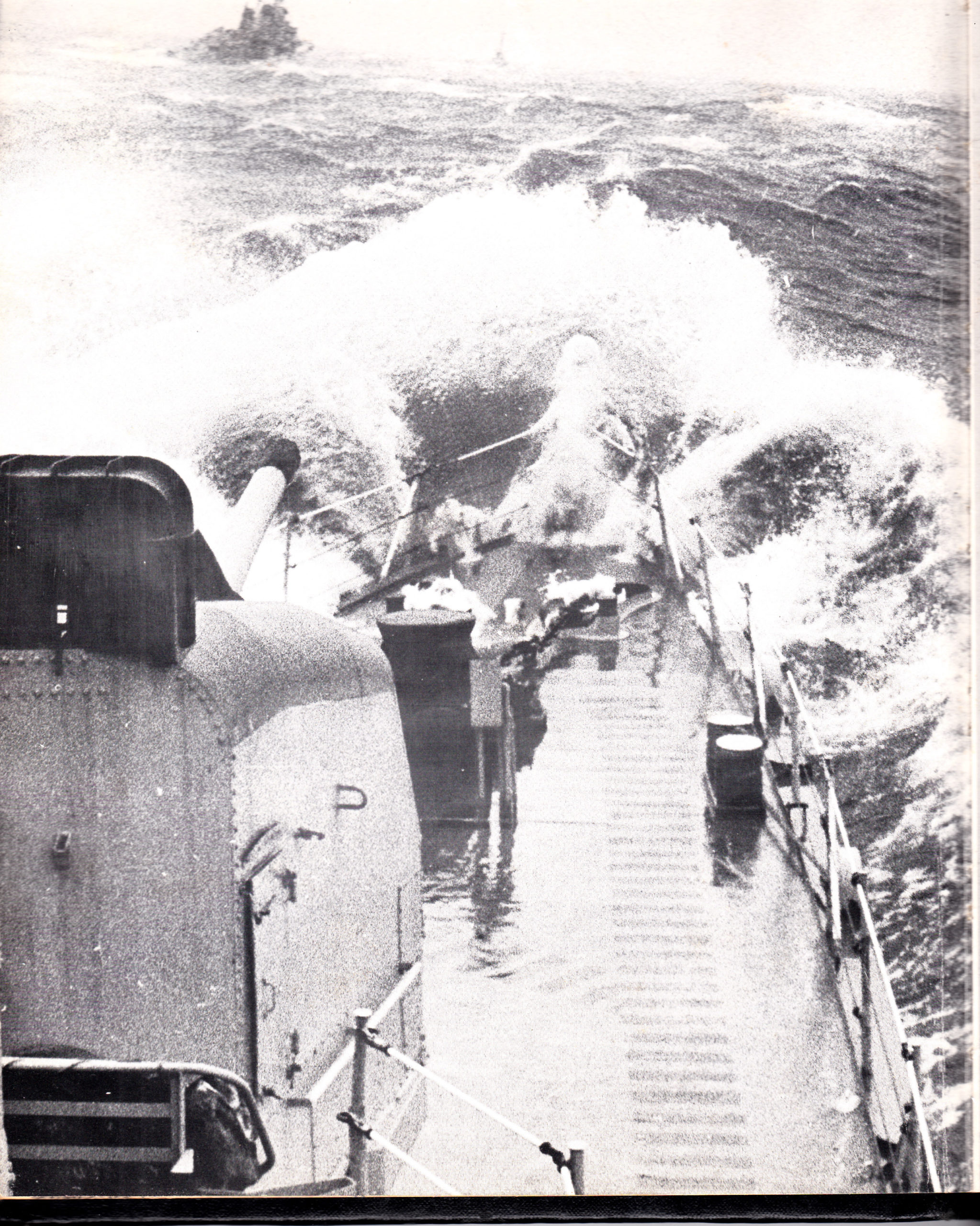

As I climbed to the Gun Director level above the bridge, I could see the oiler off our starboard bow, about a mile off. We were coming in for a refueling at sea, and we were coming in fast and close. The officer at the conn was young and green. This was my first time at sea on Shields or any ship having just reported onboard to take over the Supply Department. I was not a ship driver, but I had as much training as most 90-day wonders coming out of Office Candidate School, so I knew about getting sucked into the wake of the oiler and about maintaining proper speed and distance.

As we came alongside the oiler with the seas slamming up against the sides of both ships and green water all the way up to the bridge, I could see the Captain of the oiler standing level with us with a bullhorn in his hands. He was yelling “fall away!” and waving us off. He too knew about maintaining proper speed and distance!

Nevertheless, we continued to bring the lines and hoses across the angry gap and started to refuel. The other Captain was apoplectic! I could see he was a Commander, and our skipper was a full Captain, Howard Jackson Ursettie, USN. Amazingly, our Captain just sat calmly in the Captain’s Chair on the bridge wing and slowly waved with his palm down to the other skipper, signaling him to “calm down.”

We continued this way for miles until topped off, the oiler pulled the hoses back and we cast off the lines. With all four boilers online, we broke away and in seconds were flying through the waves with a huge roster tail rapidly leaving the oiler behind in our wake.

I had seen my first real Captain in action, calm, confident, and supporting though soon afterwards he did quietly say to the junior officer, “that was a bit too fast and too close.”